Creative Capsule Reflections — The Black Sea

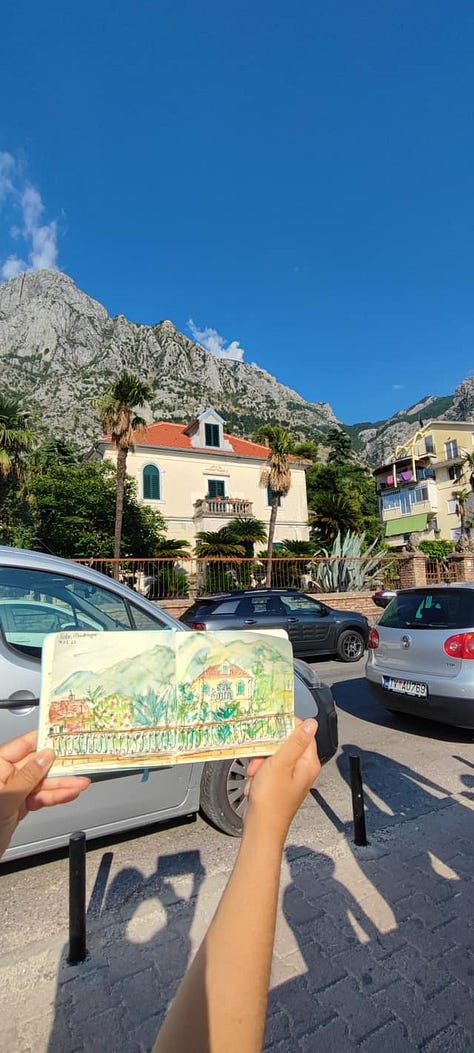

I’ve traveled to the parts of the Black Sea still available to me and watched it from afar.

Anna Romandash is a Creative Capsule Resident creating a podcast series about the Black Sea. Join her for the Creative Capsule Residency Showcase April 22, 2024 at noon Eastern. Register Here.

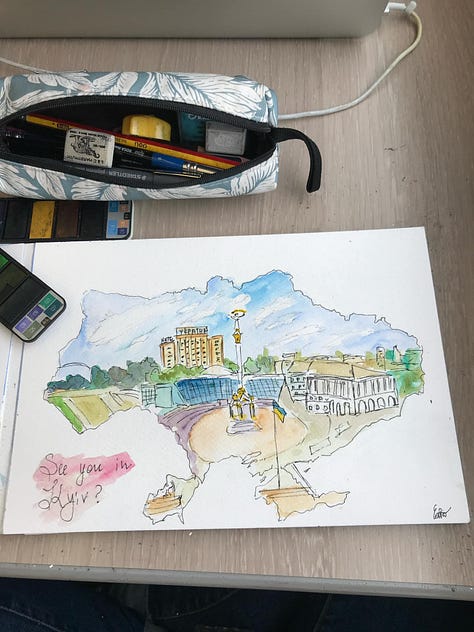

When I was a kid, I didn’t get to see the seas very much. Ukraine has two: a tiny one called Azov, and the big one, the Black Sea. Both are very far away from my home in the West of the country. Growing up, the sea wasn’t a big part of me. I didn’t miss it because I didn’t see it often.

I saw our Ukrainian sea for the first time when I was a teenager, and I was shocked at how different it was from what I had imagined. The Black Sea used to be a huge tourist destination all along the coast in the South of Ukraine — and yet, here I was, in pure cold water on a secluded and peaceful beach, and all I could see in front of me was pale blue, the color of the sky and the sea itself.

This is the memory of my only visit to the sea before chunks of it were taken from me — first, when Russia occupied the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, and then, in 2022, with the bigger invasion.

In my journey documenting the Black Sea — a part of my identity, my country’s essence, and a key to European security — I’ve met people who are losing this sea for the second or third time in their lives. I’ve visited the areas around the South of Ukraine which now host many communities that have lost their homes and their loved ones, communities that are also mourning their access to the sea and the land around it.

For my Creative Capsule Residency project I am trying to wrap my head around what the Black Sea means for Ukraine and the world, and what it represents for individuals — especially for those for whom it is the main association of home.

On this journey, I met Elzara. She is Ukrainian Crimean Tatar, born in Uzbekistan where her family was deported during Soviet colonialism, and raised in Ukrainian Crimea after the restoration of democracy. She hasn’t been to her home in years, and in her new home in Kyiv, she is building a community of those who share a similar loss. Crimean Tatars have been forced to flee their indigenous land once again, and are now working toward security in Ukraine and the Black Sea.

“It is bizarre to realize that the people and places you love are now separated from you, and you cannot just take the first flight back home,” she told me as she was sharing her experience growing up in an increasingly Russified and militarized Crimea as Russian propaganda intensified.

It was interesting for me to hear that Elzara, a child of Crimea, didn’t get to see the sea nearly as often as she wanted despite its proximity. As Crimean Tatars, her family couldn’t just settle anywhere in the peninsula that her ancestors once called their home. The family moved to Simferopol, the capital of the region, and, ironically, the furthest thing from the sunny coastal towns across the area. So for Elzara, going to the sea was a holiday, something to cherish and remember.

Elzara’s story is, sadly, typical for many of the people displaced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

On my journey, I’ve met someone who has been displaced because of war and colonialism many times and who is now fighting to restore peace and justice around the Black Sea. This man is Refat, a leader of Crimean Tatars, and a man who’s been kicked out of his home first by Soviets and then by Russians. Refat has been instrumental in mobilizing communities to fight for democratic processes on the eve of the USSR’s collapse; and he recognized immediately the threat of the Russian Black Sea fleet when Russia refused to move its navy from the newly independent Ukraine in the 1990s.

“The Black Sea and Crimea are the launching pads for the offensive, a key to the imperial puzzle,” he told me in his office, with Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar flags hanging behind his back, “It’s the main direction for Russian imperialism if it wants to control the South and expand further.”

The Black Sea is key. It leads to the Middle East, and it goes toward Europe, too. Its coasts are home to diverse people, and many of these Indigenous ethnicities have experienced inexplicable suffering as a result of the loss of statehood and pure imperial evil.

As I dive deeper into these topics, my mind becomes more and more blurry. The sea gets more complex, more difficult, and more layered. From just some ephemeral blue space it is turning into a security monster and a home base, and while I am standing so close to it, I know I cannot get closer.

“The Black Sea has a personality,” says Olena, another heroine I met on my journey. She’s an environmentalist from both Kyiv and Odesa.

“This is not a friendly sea,” she says, “It’s moody, and it can be dangerous and stormy, but it’s resilient, and it has a powerful will. It is a sea to admire.”