Creative Capsule Reflections — Where Language Fails

Art and the prison experience in the Middle East and North Africa.

Susan Aboeid and Sumaya Tabbah are Creative Capsule Residents working on a curatorial project on the prison experience in the Middle East and North Africa. Join them for the Creative Capsule Residency Showcase April 22, 2024 at noon Eastern. Register Here.

Faraj Bayrakdar, a Syrian poet and journalist who spent almost 15 years in prison wrote in The Betrayal of Language and Silence:

Sumaya: In 2023 I undertook a project translating Syrian prison language, a unique set of words that emerged during the prison experience that were documented in prison literature. In their writing, the authors document the horrors they endured, the struggle of reconciling their experiences with their reality after prison, and the effects it had on their family, among other themes. Authors consistently expressed their frustration at the constraints of their chosen medium of expression. As I observed then, “the [prison] experiences are so distinct, unnatural, and heinous, that they evoke an array of emotions that written language cannot express.” While I was immersed in the Syrian experience, the effects of carcerality extend across the region with colonial legacies, contemporary regimes using prison as a tool of state repression, and occupying powers using prisons as a means of exerting control. Palestinian survivors of Israeli occupation prisons speak of longing for home, Egyptian survivors of government prisons of the cruelty of the mundane, and Yemeni survivors of the secrecy of Houthi-run blacksites; all speak of the brutality and banality of torture.

Two questions were triggered from my visceral reaction to reading these experiences — how can any person perpetrate such heinous acts against another? What other forms of expression have survivors and prison-impacted communities turned to to express the carceral experience?

Susan: During this time, I was in the midst of studying and learning about prison abolition. The teachings and writings of Mariame Kaba and Ruth Wilson Gilmore guided me as I grappled with the question of how we, as a society, work towards abolition, transformative justice, and collective care. I was envisioning the answers to these questions beyond the US and applying a transnational perspective. It was here that I was reminded of the works of Ibrahim El Salahi and how he meticulously conveyed his harrowing experiences in prison. By rooting his art in the individual experience while also representing collective carceral experiences, El Salahi demonstrated how artists can play a powerful role in advancing abolitionist frameworks.

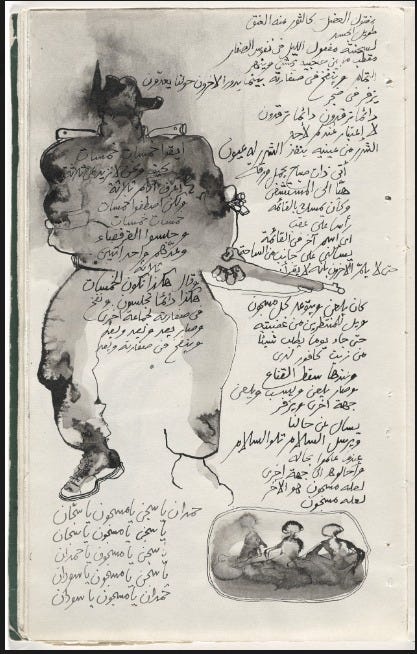

In 1975, renowned Sudanese artist Ibrahim El Salahi was arrested by the Nimeiri regime and taken to Khartoum’s infamous Kober Prison where he remained for six months without trial. After his release, El Salahi was placed under house arrest. It was during this period that he began processing his experience, he writes, “When I was released at last, every single night I woke up from these horrible dreams. That is what made me start making small sketches, small abstracts of color.” His works, a series of sketches, poems, and commentary were compiled in the 1976 publication Prison Notebook.

It was this thread of commonality across the prison experience in the MENA region and the use of art as a tool of reconciliation and abolition that brought us together and inspired our curatorial project, “A Prison, a Prisoner, and a Prison Guard:” An Exploration of Carcerality in the MENA Region.

Our exhibit title borrows from El Salahi’s untitled poem, first documented in his Prison Notebook. The poem is about a prison guard named Hamdan, whom the author seemingly feels sympathy towards. El Salahi recounts how every morning Hamdan, who was illiterate, would wake up the prisoners at dawn and count them in groups of five.

Prison Architecture

In the poem, El Salahi blurs the lines between prisoner and prison guard, as well as between victim and perpetrator. He metaphorically expands the prison beyond what occurred “within those very, very high sandstone walls,” to all of Sudan. In his commentary for the poem and the drawing, El Salahi writes, “Because what was happening to [Hamdan], what was happening to us — we were all in a big prison.”

We want this exhibit to break down and reconstruct the viewer's understanding of the “prison.” We want people who visit the exhibit to redefine and reimagine what they envision the prison to be. Could a diplomatic mission house be considered a prison? What about an old airport? A world heritage site? A school? Society as a whole?

What is Prison Art?

Nicole R. Fleetwood, curator and author of Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration uses the term “carceral aesthetics,” to describe “the production of art under the conditions of unfreedom.” These conditions, such as “penal space, time and matter,” become both the raw material and the subject matter for prison art.

It is through this understanding of carceral aesthetics that we see the creation of art as politics, as a way to produce meaning under hostile, traumatic and brutal circumstances.

With Fleetwood’s conceptualization of prison art in mind, we asked ourselves the question “What is prison art?” Was it art created in prison, art created after prison, art created about prison? Did the artists have to be imprisoned or formerly imprisoned? How do we define and set parameters for an entire category of art?

Further still, many of those who produced “art” in prison would not consider their products art or themselves artists. What does it mean then, for us to categorize them as artists and their work as art? As we explored these questions, we drew parallels from our experiences working with prison literature where the same debate carries on.

Collective Efforts, Abolition, and Reconciliation

Widening the scope of how we defined “prison art” allowed us to conceptualize an exhibition that through its width and breadth explored the impact of prisons not just on individuals, but also on countries and communities across the MENA region. By zooming out, we attempt to show that carcerality is not an entirely unique experience that differs much depending on the country or regime. This was in an attempt to encourage drawing parallels in the experience of survivors across the region rather than hesitating, for example, to compare the Syrian regime’s prisons with those of the Israeli occupation.

Through the comparisons, we are able to highlight the intentionality of carceral systems and bridge the gap between and across activist spaces in the region. The wider breadth allows us to resist notions of individualism in carcerality and instead expand the conversation to include prison-impacted communities as well.

This art exhibition attempts to both address the how and the why behind harm on both an individual and societal level. As Kaba writes, the criminal punishment system depends on a “facile view of good and evil based on the victim-perpetrator binary.” Interrogating how an individual and a society perpetrate this kind of violence also informs how individuals and society move on after experiencing and perpetrating violence. This understanding pulls from reconciliatory frameworks that recognize that abolition occurs on a communal level, as well as an individual one.

As we engage with and curate the art we recognize that there are distinct political, governing, generational, social and cultural structures across the region that informed the inception of certain pieces and their intended perception. We hope to stay true to these conditions and communities while resisting the othering, and oftentimes orientalizing, gaze by rooting our understanding in a universal abolitionist framework. To do this we attempt to show that the barbarity of the carceral systems found across the region are in fact a barbarity and a form of savagery consistent with all carceral systems.

Looking Ahead

Our hope in curating this exhibit is to further artists' original goals — healing the wounds caused by the violence of prison, documenting their experiences, and expressing through art what may be impossible to express through words. In the words of Gilmore, we hope to show through this exhibit that “where life is precious, life is precious;” even in the darkest, bleakest cells of society. Here, the creation of art is a representation of one’s life, under unimaginable conditions.

Where language fails to capture the enormity of harm, so too does silence. It is through art that we attempt to convey these experiences, in all their layers and complexities.