Critical State: Orbán’s Occupation

If you read just one thing … read about Viktor Orbán’s plans for Europe!

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has a long and fraught history with the European Union. As Kim Lane Schepple describes in a recent article in the Journal of Democracy, “While the EU proclaims itself a union of democracies that value the rule of law, Orbán has undermined the union, democracy, and the rule of law.”

In 2022, EU officials “froze nearly all the funds that Hungary receives from Brussels. … After the EU started hitting Orbán where it hurts, he faced a threat to his solid grip on power at home as one of his own party faithful broke ranks and created a political movement that has quickly challenged Orbán’s political monopoly.”

Orbán, per the article, has fundamentally not changed his behavior, instead “wielding his veto repeatedly to extort the frozen funds from Brussels rather than make the changes to earn them.” Though Orbán often bashes Brussels, it is EU money that makes his rule possible, the article argues, as he needs to be able to give EU funds to his supporters in the form of lucrative contracts. And for this reason Orbán is battling with Brussels — while also taking on a challenger at home: Peter Magyar, a former Orbán ally, who is “no liberal” but has “attacked in equal measure Orbán’s self-serving ‘mafia state’ and the Hungarian left’s cluelessness about the countryside.”

Our Atrocities

In The Nation, Bruce Robbins asks if a cause can remain just if atrocities are committed on its behalf.

Robbins opens with photos of German cities bombed by Americans during World War II: “Why are these images missing from the collective memory? Is it because the United States had no photojournalists in enemy territory? Or are they unremembered because, unlike so many of the bombing campaigns that followed, this one belonged to what we think of as a good war? Most US readers probably have little desire to contemplate the collateral damage, measured in German civilian lives, of a victory over fascism that everyone agrees was noble and necessary.”

He goes on to argue that you can’t understand history, or violence, if you only see guilty perpetrators and innocent victims. Still, even “if atrocity does not make a cause unjust, it does not follow that the existence of atrocities can be ignored. To commit an atrocity is still the single worst thing anyone can do.”

Laughing Matter

Nigerian comedy is getting serious, writes Oyedele Alokan for Africa Is a Country.

“Nigerian stand-up comedy didn’t start out offensive or daring. It slowly evolved as a side attraction from the days of Alarinjo theaters, where comedy skits were featured between acts of stageplays. Then it morphed into the well-dressed and dapper JC, who owned the first comedy club in Ikeja, Lagos. Stand-up comedy has never been a viable profession,” explains Alokan.

However, “the art form continued to feature prominently in nightlife and events such as weddings, namings ceremonies, galas … virtually every occasion where people gathered.” And though established comedians saw comedy as an end unto itself, eventually, “By the time Instagram became saturated with content creators, a new crop of young people had begun to take interest in stand-up comedy again. Not just as entertainers, but as artists who believed their opinions mattered. … The new comics who make up Nigeria’s comedy circuit have learned from their predecessors. They place more value on intellectual property and the delivery of their art.”

Deep Dive: Palermo Patchwork

For five non-consecutive terms, up until 2022, Leoluca Orlando served as mayor of Palermo, the capital of Sicily. In that time, Orlando put forth a “cosmopolitan vision of local identity” — in other words, that the city had an essence, and that that essence was multicultural. In “‘Palermo is a mosaic’: cosmopolitan rhetoric in the capital of Sicily,” a recent article in the journal Modern Italy, Sean Wyer writes of Orlando’s message: how he communicated it, why he saw utility in it, how it was received, and the risks “inherent” in insisting that a city has a true nature.

Orlando was hardly the first to embrace this image of Palermo. As Wyer explains, “Sicilians often emphasize the intricate cultural ‘mixity’ of their island, resulting from its history as a locus of invasion, and its long experience of emigration and immigration.” But Orlando, one of Sicily’s most recognizable politicians, amplified the idea. Wyer argues that this fight against intolerance has been linked to another of Orlando’s struggles: that against the mafia.

Wyer was particularly interested in Orlando’s social media posts, and namely his Facebook missives. He has over 85,000 followers on the platform and, since 2012, has posted thousands of times.

Wyer puts forth that Orlando made his case with a combination of past and present: “To construct a vision of Palermitan local identity, Orlando draws connections between periods in Sicilian history and Palermo's contemporary reality, arguing that these demonstrate characteristics inherent to Palermo and its inhabitants.” Orlando tried to argue that fascism and even the mafia were an “aberration” in Palermo’s history.

For some of his commentators, using Palermo’s past to justify an openness in the present made sense: One commentator wrote, “Everyone who comes to Palermo ‘Palermitanizes’ themselves, and often the Indians and the Senegalese speak our dialect better than we do.” But others rejected that such parallels between past practice and present policy existed: As Wyer notes, “One commentator emphasizes that any convivenza in medieval Sicily was short-lived: Frederick II (1198–1250) expelled Sicily's remaining Muslims to the mainland. It is by no means straightforward, in other words, to determine what lessons, if any, can be learnt from Sicilian history.”

Orlando tried to use rhetorical as well as historical arguments, comparing the city to a “mosaic,” which, as Wyer notes, is an important art form in the city, core to its cultural identity. Again, though he was not the first to use this line, he amplified it: “Each tile makes a distinct and necessary contribution to the whole. The whole, in turn, is not only capable of incorporating contradictions, differences and tensions, but requires contrasts to convey the desired artistic effect: the whole mosaic is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Orlando’s posts were used symbolically (to inspire a kind of ethos in and toward others in Palermo) and practically (to promote concrete political platforms). Wyer asks whether the effect is to put forth an inclusive vision or, alternatively, whether it is self-congratulatory, obscuring actual xenophobia on the island. Perhaps the answer is both. “This identity narrative will continue to be articulated, reshaped and contested over the coming decades,” Wyer writes, “whether or not elected representatives continue to play an active role in promoting it.”

Show Us the Receipts

Hannah McCarthy wrote on how some Israelis are using this precarious geopolitical moment to seize and settle more of East Jerusalem: “Since the war in Gaza began last October, the Israeli government has backed settlement activity that has accelerated across East Jerusalem, fracturing Palestinian communities and threatening the territory’s viability as a capital for a future Palestinian state.” Contested sites include the Old City; the Mount of Olives; Silwan; and Sheikh Jarrah. Some use force; others use “courtroom battles” and “legal tactics to uproot Muslim and Christian residents of the Old City.”

Daniel Ofman reported on tensions between the United States and Russia and how the two countries came to be in a situation with little arms control and still less communication. In 2019, Russia and the US, each accusing the other of non-compliance, withdrew from the INF Treaty. Meanwhile, a “range of other agreements and treaties on arms control have also expired. At this point, only one arms control treaty, ‘New START,’ remains on the books — and it is set to expire in 2026.”

Rose Gilbert looked at Kurdish newcomers to Nashville, Tennessee, bringing their own sound and cultures to the country music capital. As Gilbert explained, “Nashville has the largest Kurdish population of any city in the United States, and most are from the Iraqi region of Kurdistan, known as Bashur. They arrived in waves starting in the 1970s, with the largest influx prompted by Saddam Hussein’s genocidal campaigns in the late 1980s and early ’90s.” There’s been an uptick since the coronavirus pandemic. The journey is difficult and resettlement is, too — but Gilbert described how there is music and culture on the other side.

Well-Played

Mais oui.

And we’re going for gold.

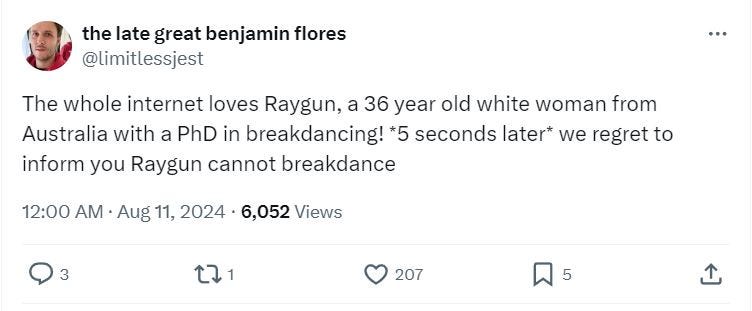

We regret to inform you.

It’s time for Lutheran chat.

My job? It’s just post.

A lot of great things happen, too.

Critical State is written by Emily Tamkin with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news, and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.