When a Lockheed job was (almost) better than a Caribbean romance

Some stories about the golden years at Lockheed Martin in Marietta, the local Machinists union's dwindling ranks, and why a storied union family’s descendant “would never recommend” a job there now.

Hi,

Today I want to share some of the colorful stories I’ve been hearing alongside my Inkstick colleague Dr. Jennifer Greenburg, who is leading a nationwide study about public opinion on military spending, national security, the effectiveness of federal spending on defense, and citizens’ priorities with tax dollars. I’ve been working with her in Marietta, which hosts a major Lockheed Martin aircraft plant — that’s the world’s largest defense contractor and the largest recipient of US taxpayer money.

First, a quick introduction to Marietta: The sprawling suburb of Atlanta is the seat of Cobb County, nowadays the third-most populous county here in Georgia. A pivotal transformation of Cobb’s economy occurred in 1941, when, following a lobbying campaign by local boosters eager to industrialize the area and lift it out of the Great Depression, the federal government agreed to build an airstrip in a then-rural locality. That was followed by the construction of Government Aircraft Plant 6, which rolled out hundreds of Boeing-designed B-29 Superfortresses during WWII. The busy plant transformed Marietta into one of the largest aircraft manufacturing sites in the world.

Intertwined with Marietta’s military-industrial turnaround was another key player in the defense industry: the Machinists Union, which has its origins in the 19th-century Atlanta locomotive sector. Lockheed reopened the (slightly renamed) Air Force Plant 6 during the Korean War and the boom in military spending that the Cold War ushered in. The Machinists started to represent its blue-collar workers in 1961. In the decades since, the plant has rolled off assembly lines an assortment of military aircraft, including 2,600 C-130 Hercules, the cargo plane used to evacuate people from Kabul as the Taliban retook the country in 2021, and 187 F-22s, a fighter jet recently used to shoot down a Chinese balloon off the coast of South Carolina.

We were recommended a really nice book during the course of this research, “Lockheed, Atlanta, and the Struggle for Racial Integration,” by Kennesaw State University history professor Randall Patton. I drew much of the history above from it, and have really enjoyed reading it — the book reminds me of another favorite, “Cold War Dixie,” about the construction of a nuclear weapons plant in rural South Carolina. I’d love to see more deep-dives into defense industry towns like these.

“Men, they come a dime a dozen. But those jobs at Lockheed?”

Dr. Greeenburg and I spent three days at Local 709, a single-story beige office building with an adjoining auditorium and an enormous parking lot the union’s staff told us is sometimes used for motorcycle shows. In its worker power glory days of the 1960s and ‘70s, the auditorium would be filled for three days straight as about 30,000 members filed in to vote for union leaders. Nowadays, monthly meetings draw about two dozen or so attendees, and membership is down to about 2,000. You can read more about union-busting at this plant and other defense contractors in my investigative report from last year, Union Strength Dwindles at Top Defense Contractors.

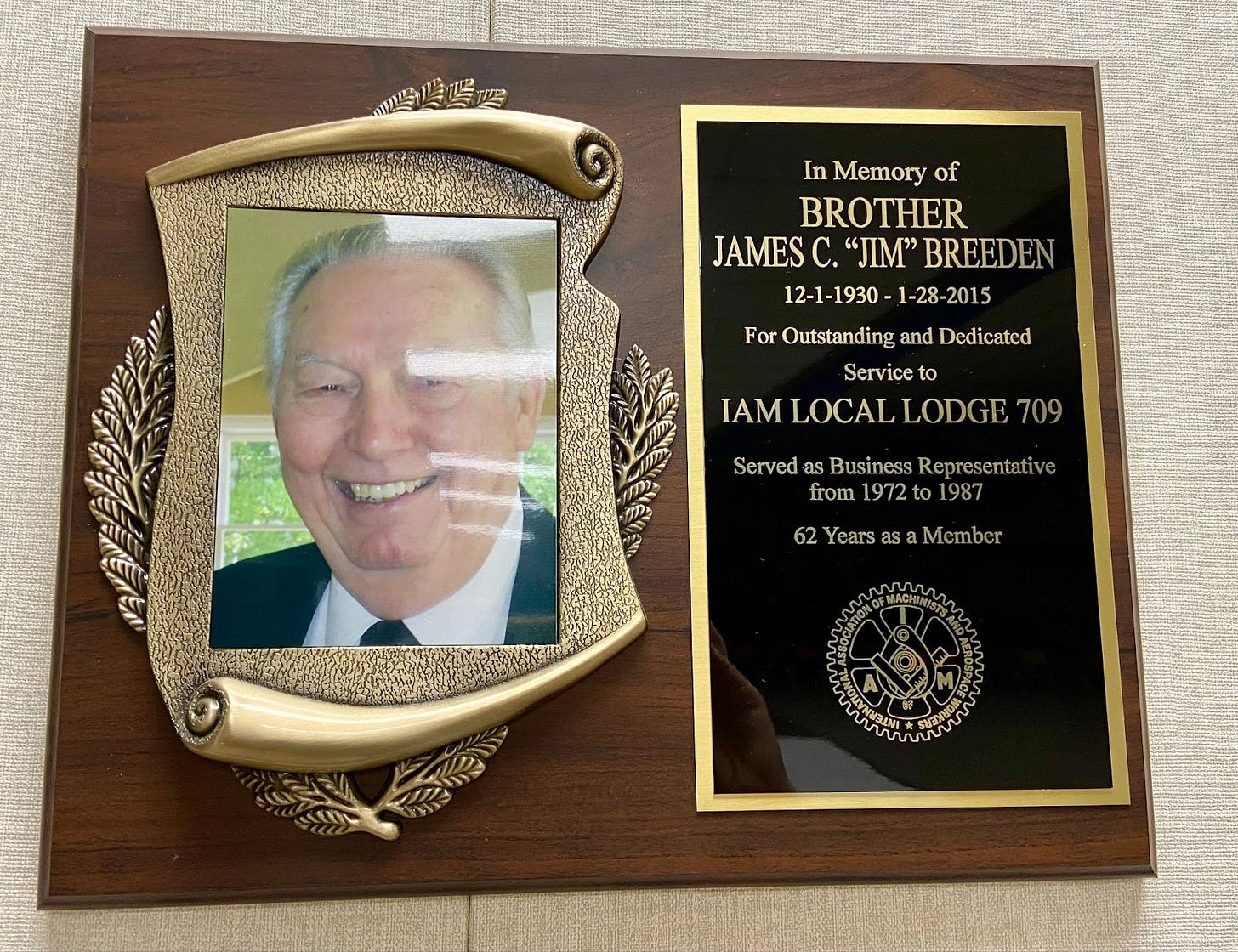

Plaques for past union officials at the entrance to the auditorium

We wanted to hear the story of then and now, and we found a delightful oral historian in Becky Taylor (neé Breeden). Her time at Lockheed dates back to 1979, and she’s nowadays the union’s secretary. She was one of 10 extended family members employed at the sprawling plant, where a sign at the entrance read: “Through these gates pass the greatest aircraft workers in the world.” It was a time when raw materials came in one side and aircraft flew out the other, a contrast to the vast subcontracting web that nowadays splinters work on a given plane across numerous states. Workers at Local 709 told us that in the future the plant will still receive parts from outside subcontractors, but that they will have pre-drilled holes and be assembled by robots rather than blue-collar humans.

The Breeden clan earned legend status at the lodge after Becky’s father won a record six terms as the union’s Business Rep. During his final election, members drew up a snarky cartoon of the plant’s entrance, captioned: “Through these gates pass Breeden and family.”

Becky Taylor (left) at her father’s retirement party. Courtesy of Becky Taylor

Becky said she was hired at a time Lockheed had quotas for women, and she was soon employed as a drill bur, boring small holes on aircraft parts. She was in awe of the vastness of the plant, where as far as she could see thousands of people were working on planes and wings. When the bell rang, about 10,000 people would beeline for tunnels to exit the plant, causing a local traffic jam.

Becky said the Breedens weren’t the only clan on the inside, because if you could get your relatives a good job, you did.

“Everybody in there came from [someone who referred them], their father worked there, their grandfather, someone in their family, because if you got a job at Lockheed, at that time period, you could go anywhere in Cobb County and say you worked at Lockheed and they'd give you about anything you want,” she told us. “I drove a car off the car lot because [Lockheed] had their own credit union. ‘You work at Lockheed? We'll make one call. Take the car. We got it under control’.”

Becky’s story of the financial safety net of working for a company town’s aircraft manufacturer was echoed by retirees we met at a Tuesday luncheon. After saying grace and the Pledge of Allegiance, we joined about a dozen old-timers for a potluck and a raffle. Many of the retirees were Black and told us that getting an in with Lockheed was a precious ticket to economic mobility.

One retiree was hired, like Becky, in 1979, when she was just 19 and had a two-year-old. She lived two hours away in Rome, a mountain town in north Georgia that is best known nowadays for being the political home of far-right US Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene. The mother told us she was funneled into Lockheed by taking part in the federally funded Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). She didn’t know at the time that Lockheed made planes, let alone military aircraft. What she did know was that her hourly pay doubled the day she walked into the plant. Her manager threw “a cussing fit” when he saw her in the machine shop, she said, angry to see a Black woman assigned to him. He handed her a broom and told her to sweep, which she did. “Back then you were just glad to have a job,” she told us.

She made enough money to leave Rome for Atlanta, where she would rouse her daughter before the sunrise to take her to a special daycare that opened early for manufacturing employees. She went on to ascend to labor grade 12, became a shop steward for the union, and stayed 20 years at Lockheed, earning the pension that supports her today.

A second retiree told us that he was hired as an aircraft painter while he was still illiterate and needed his sister to fill out his job application. A local public library found him a reading tutor, who used the Bible to teach him phonics. In the meantime, a coworker encouraged him to take a blueprint reading class at Lockheed; he did so and became a quality inspector. He worked at Lockheed for 39 years and four months.

Their stories of swapping teenage motherhood in rural Georgia and adult illiteracy for a solid, enduring foot in the middle class helped me to understand the deep loyalty to the company, or at least to what the company was.

Becky was a little more deviant. One day, she approached her father with something she knew he wouldn’t want to hear. “Daddy, I said, I’m going to quit Lockheed. I’m going to get married. I’m in love.” And that love was in the sunny Caribbean nation of Belize.

“Honey,” he said, “you’re a pretty, hard-working woman. Any man would be happy to have a wife like you.” He went on: “Men, they come a dime a dozen. But a job at Lockheed?”

He was serious. He would eventually spend half a century working at Lockheed. He convinced his daughter to take a leave of absence rather than quit, and Becky indeed followed her heart abroad. She returned to Marietta years later with a daughter and happy memories she said she’ll never regret.

“Now, I would never recommend it”

Those are the types of stories of the Lockheed of yesteryear that we heard over and over in the union hall. We went there to talk about defense spending and national security, but some of our most fervent conversations were about job security. It reminded me of an essay by Conor Ryan, a defense policy researcher turned Naval officer:

The American people care most about jobs, and not any other policy. According to a 2014 report by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs: Protecting the jobs of American workers has been among the top foreign policy goals considered “Very Important” in all 14 surveys since 1974, placing first in no less than eight polls — higher than preventing the spread of nuclear weapons and combating international terrorism.

And a job at Lockheed in Marietta now isn’t what it used to be. The retirees told us they don’t think their modern-day counterparts will be gathering for the pledge of allegiance and potlucks 30 years from now. The union told us about several ways the company has chipped away at their numbers and their morale, a decisive one being the elimination of pensions in 2011. Turnover outpaces onboarding as new hires decamp for companies like Delta. Lockheed recently announced hundreds of layoffs at three locations, including Marietta. (A company spokesperson didn’t give me precise numbers but told me the layoffs in Marietta were “a handful” and that some of the affected workers found other roles in the company.)

Their stories track with the data. Employment in the private defense industry has plummeted from three million in 1985 to 1.1 million in 2021, according to the National Defense Industrial Association. And according to the NDIA, the remaining jobs didn’t pay better but actually worse: Inflation-adjusted average salaries dropped from $100,500 to $96,994 over the same time.

Among other things, Becky resents the company’s current “four-ten” schedule, which she thinks is worse than the traditional five-day, eight-hour week for Lockheed’s working parents. That includes her son-in-law, now a single parent to three children after Becky’s daughter passed away.

He has to be out the door at 5:30 am and doesn’t get off work until 4 pm. She said it’s a similar story for many other working parents who can’t afford to live in increasingly affluent Marietta and are in cheaper suburbs an hour away. “They're taken away from lives, from families. And I just think it goes against everything that God wants for us in our lives,” Becky said.

“Now, I would never recommend it,” she said about working at Lockheed. “That’s how much it’s changed.”

What I’m following

Something about the Northrop Grumman-Waynesboro deal doesn’t add up

A small town in Virginia recently announced a deal to give tax breaks to the world’s third-largest weapons maker, Northrop Grumman, in exchange for it building an electronics plant and testing facility that will supposedly create 331 new jobs. Bulldozers have already cleared land for it behind a Target and a Petsmart in Waynesboro, pop. 22,808. Local university employee and watchdog Nick Patler obtained the economic development contract through a public records request and found that the job creation incentives in it looked sketchy. “If the moral or ethical issue of a killing corporation in our backyard doesn’t move you because you see dollars,” he wrote, “what will your reason be as those dollars slip through the holes in this agreement?”

How to transform a war economy for peacetime.

I enjoyed hearing friend and mentor Miriam Pemberton on NPR’s Planet Money, where she discussed when the US has occasionally attempted an industrial policy to beat swords into plowshares.

Thank you for reading!

Thoughts, comments, story suggestions? Send them my way at tbarnes@inkstickmedia.com. We may publish them in a future newsletter.